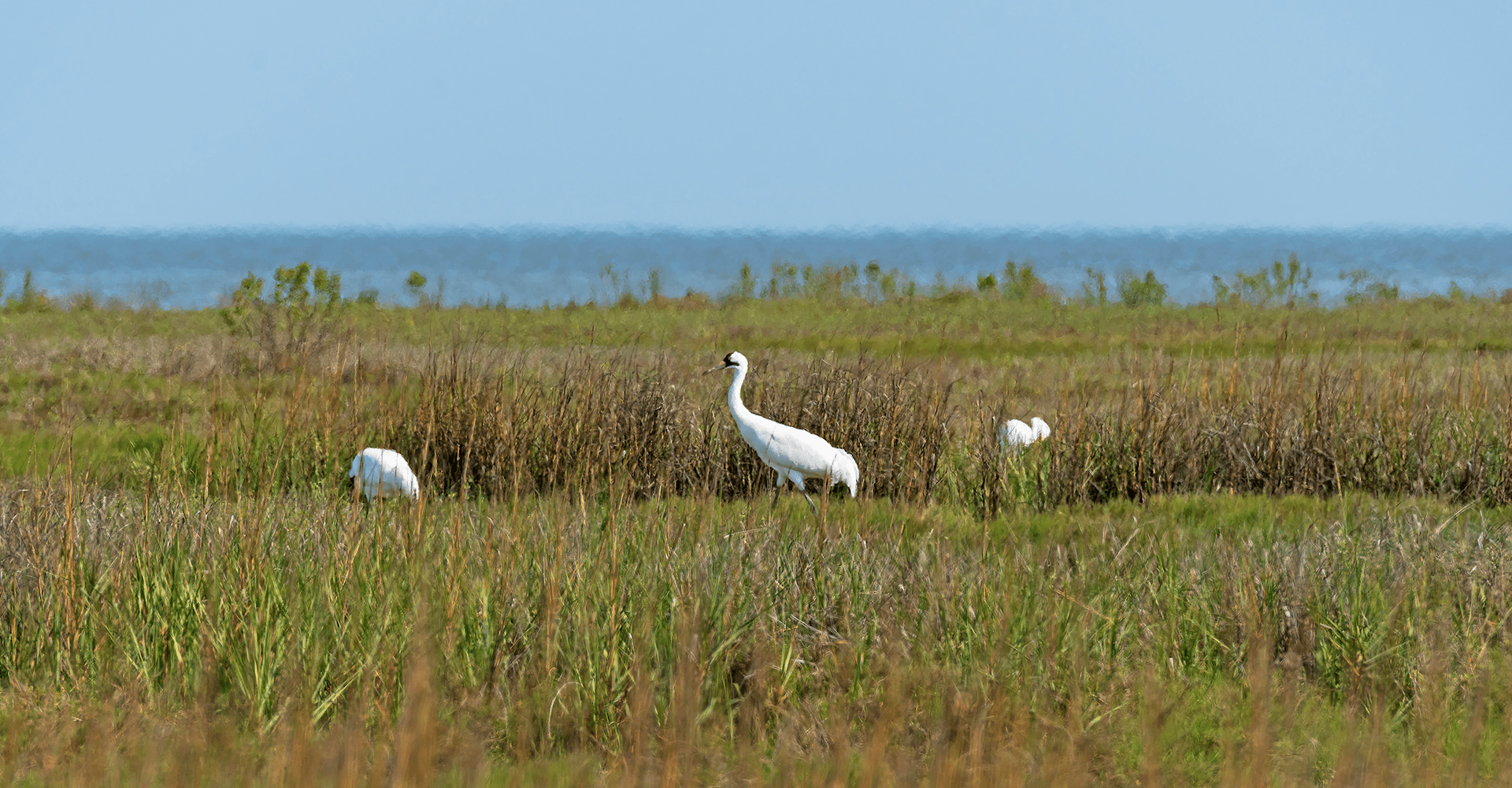

Mangroves, a habitat consisting largely of shrubs and trees, are encroaching on Galveston Bay’s saltwater marshes. The marshes support wildlife, notably the endangered whooping crane, often sought out by regional birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts. The cranes find mangroves particularly difficult to thrive in, since predators are more likely to hide in their forest-like covering.

However, these same mangroves may help to mitigate flooding events by protecting the shoreline from erosion. So, are the slowly expanding mangroves a good thing for the city of Houston? “That’s the question we’re trying to answer,” said Steve Pennings, UH biologist.

Pennings and collaborators are using several factors to determine how the ecosystem of the estuary and bay contribute to Houston’s well-being and oftentimes, its detriment. For one, as a mangrove habitat spreads, whooping cranes and other wading birds may have to move to other locations. Pennings has studied these types of habitats for years, in Europe and China, as well as in the U.S.

There are many other reasons the mangroves of the southern tip of the state are so important – they hold carbon in their soil, purify the water through complex chemical reactions and support many other species – including those of the fish, mollusk and bird varieties.

Mangrove trees die during hard freezes. Until a year ago, the Texas coast had not had a hard freeze for decades, and it appeared that mangroves were inexorably spreading to take over salt marsh habitat. However, as a result of last year’s severe freeze, mangroves have died over large areas of the Texas Coast. Pennings and his collaborators, including Dr. Anna Armitage at Texas A&M University at Galveston, are now studying the impact of the freeze on intertidal wetlands near Port Aransas. Surveys taken in the fall of 2021 indicated almost complete mortality of adult mangroves, but substantial numbers of new seedlings. They expect that this year they will see a marked increase in salt marsh plants, which are no longer in competition with the mangroves, but also continued growth of new mangroves. How quickly the mangrove forest will recover and look the way it looked before the freeze is unknown.

A decrease in wading birds and a likely change in fish communities caused by the spread of mangroves might be considered a bad thing. But with the protection against rising waters that mangroves offer, and because of the awful economic toll storm-driven flooding takes on the Texas coast, the spread of mangroves might be something local residents would welcome.

Plants are dried and ground up, samples are bagged and taken back to the UH laboratory and large plots of land near the estuary in Port Aransas are roped off for field studies. The research done by Pennings’ lab is published and presented at such conferences as the State of the Bay Symposium. Biologists and ecologists process the information, but the data is important to every resident of Houston – and every critically endangered whooping crane, as well.

Image Credit: Getty Images/iStock/Wildnerdpix