There’s something happening on the UH campus. Just over the freeway, on the other side of the tracks, there’s a part of UH that is setting Houston’s tech and science world aflame. The Technology Bridge. A place where academia meets the market thanks to a program designed to connect both worlds: the Connectivity Program.

The Bridge

In the latter half of the 19th century, post-Civil War, the US economy was booming. Money backed by gold, the Legal Tender Act, railroads, steel, and a burgeoning innovative spirit fresh off the heels of the Industrial Revolution patched up many of the holes left by the Civil War. Labor was in demand, especially in big cities like New York. New York, with its five boroughs, presented a unique problem to hopeful and ambitious workers: the only way to get around was by ferry. This limited form of conveyance caused some people to seek employment closer to home. Unfortunately for Brooklynites, the jobs were really aplenty in Manhattan.

One man would change the fortunes of Brooklynites hoping to find work in Manhattan: John A. Roebling. The man that designed the Brooklyn Bridge. Upon its completion in 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge allowed people in the city to more easily travel to jobs in Manhattan and vice versa. It connected the borough with the most people (at the time) to the borough with the most jobs available.

Soon, Manhattan flourished. New York City was reborn. It was primarily thanks to the Brooklyn Bridge. The great connector.

The same thing is happening right now on the University of Houston campus.

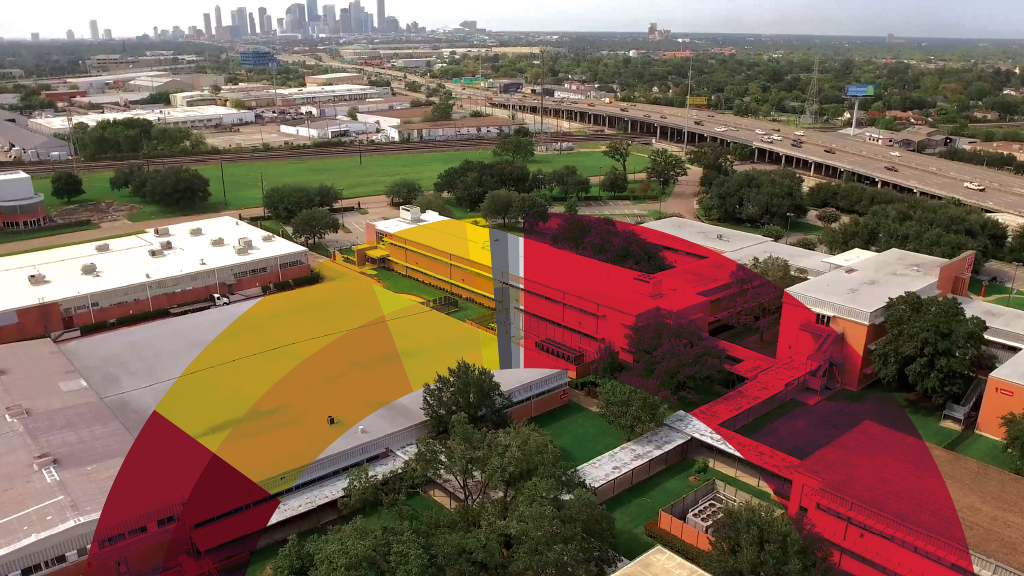

Just east of the UH main campus, a mere 12 minutes away, lies a 700,000 Square-Foot space suited for laboratories, pilot-scale facilities and manufacturing. Behold; the Technology Bridge. “One of the reasons we use the name bridge is because it’s a bridge from the academic world, one step closer to the market. It bridges the gap between research and commercialization,” explained Tom Campbell, former executive director of the UH Office of Technology Transfer and Innovation.

Some might remember this space being Energy Research Park. The beginnings of a Powerhouse campus. Now, that area is a hub for innovation and the campus’s nucleus for tech transfer.

“The initial push for the Energy Research Park was to build momentum and create a critical mass of companies. We achieved that. But then we started looking and we found that these companies didn’t have a real close association with the University of Houston,” Campbell said.

The Connectivity Program

Campbell spearheaded an initiative to lasso together UH faculty and business executives. Researchers with entrepreneurs. Scientists with businesspeople. This initiative is called the Connectivity Program. It is a way to form a community of people that exchange ideas and form business relationships. It offers startups a quid pro quo in which they find ways to connect with UH and in return, UH faculty provide them with their unique scientific expertise.

“One of the reasons for attracting this community of people is, you want to try to bring companies in so that you give them the opportunity to learn, but equally so, the university gets an opportunity to learn,” Campbell proclaimed.

“The co-mingling of UH faculty startups and startups outside the university is a positive thing because they each learn from one another. By incubating them in the same space, it creates an innovation ecosystem where faculty who are inclined to create startups can have a place that’s just a stone’s throw away from their academic labs. They can teach during the day, and during the evenings and weekends they can come over to the Technology Bridge and actually try to commercialize their technology and take it forward. You now have a bridge that brings you one step closer to the commercial world.”

Commercialization of Technology

There are two primary channels through which startups come into the UH incubator: faculty startup and startup. A faculty startup is a vehicle to commercialize UH research. Why would a university care about that?

“Lots of inventors and faculty members want to get their ideas out into the market. The ideas are super early. Early-stage stuff. So this thought that it’s two years in your garage and it’s ready for market, that’s more like five to ten years of really painful work. It’s not like opening a new restaurant or dry cleaning service. These are early-stage, research-based startups that are deep technology-based,” warned Campbell.

Five to 10 years is a long time. That’s about two bachelor’s degrees. Two presidential terms. Two World Cups. With such a long time of investing money, emotions, pain, you’ll need a place to put everything together. A place you’ll probably make your second home in that span. You’ll need an incubator.

“Acquiring startups into a university incubator creates an entrepreneurial or innovative spirit within your faculty. A company might need the technical expertise of UH faculty and, in turn, UH faculty will learn from an entrepreneur’s startup execution experience. It’s a win-win. There’s got to be a natural synergy to make it work.”

It might surprise you to know that most of the products in your house had its origins in the technology that came out of a university. Your toaster oven, window cleaning liquid, paint coating and myriad other things were all in some way or another created from university-based technology.

“Universities create ideas and technology and companies create products. If you’re going to commercialize your product and bring it to market, you’re going to have to do it through a company. There is no manufacturing group at UH,” explained Campbell.

“And by the way, all the big national funding agencies are all now asking for commercialization plans. What do you plan to do with this work? The reason for that is that they have to talk to Congress. Since it’s a lot of taxpayer money funding long-term research, they want to be able to show these discoveries are getting into the market and making the world a better place.”

The Four Tiers of the Apocalypse

Campbell explained that his team created the Connectivity Program because he questioned the value they were creating with this fee-based model for startup incubation.

“We knew the value was related to connectivity, so we created the connectivity program,” he said. The program is a way to establish a connection with a company when we bring them in. It’s not just about the rent; that’s part of it because we do have to offset costs. But it’s more about what kind of relationship we can build with that company while they reside here.”

So, Campbell came up with four tiers that would determine the fate of startups. Either they form a connection with UH in some way, or they see an end to the partnership. It’s actually how most romantic relationships work. No connection, no future.

Tier 1

Startups that are trying to commercialize UH intellectual property. These startups are all about taking UH ideas that originated on campus and bringing them to market.

“If you are commercializing UH technology you get a break on your rent price,” revealed Ryan Black, the program director for The Bridge.

Tier 2

These startups offer a deeper level of engagement. They sponsor research on campus or create relationships with faculty members to get them engaged in the company. These startups represent a higher level of connectivity.

Tier 3

These companies have formed relationships with faculty but have no technology.

Tier 4

The Connectivity Program allows Tier 4 companies to apply whether they have UH technology or not. Startups in this tier are notified that if they don’t create some level of connectivity with the university, their trial will be terminated.

“We don’t want to just move companies in and have a long-term rental relationship with them. We want companies who have some interest in UH. It’s got to be a win-win. A win for the company and a win for UH,” Campbell said.

Survey Says: Success!

The Connectivity Program has incontrovertibly been a rousing success, with only two private labs short of being 100% full for the first time. True to form, the Connectivity Program has played the role of a bridge in merging two worlds: the academic world and the business world.

The program has helped companies like RevoChem develop and grow their business beyond Houston. RevoChem has, in turn, fostered their connection with UH by hiring science and business graduates from the university.

“I can honestly say, RevoChem would not be possible without the Connectivity Program. This program helped us attain a laboratory to test our ideas, which have now become successful commercial products used by more than 20 oil and gas companies, including many big ones such as Chevron, ConocoPhillips and Occidental,” attested Fay Liu, founder and CEO of RevoChem LLC.

“The Connectivity Program made the UH incubator a great resource not just to the university but to the entire Houston area. We have even hired four UH graduates with science and business backgrounds after joining the program,” she added.

Oleon is another great company that has made great strides with their connection to UH.

“UH Technology Bridge has offered Oleon a landing spot in Houston for us to start both our business and R&D work. It is a rare find in Houston to have both office and lab space available combined with a fishing pool of talented students. I think it is a great initiative to bring together the resources of the University with those of the industry. Clearly a win-win for both sides,” said Dave Jacobs, general manager of operations for Oleon.

When asked about the gravity of university incubators and why entrepreneurs are drawn to them like bees to pollen, Campbell expressed that universities represent the very progressive spirit that is congruent with that of young, starry-eyed startup entrepreneurs.

“There’s a tremendous amount of collegiality and goodwill that comes from this group of people. They migrate to a university just because they feel that a university is about bringing new ideas and new people (graduates) into the world, trying to do something good,” he said.