There is a sport where two individuals clash in front of thousands of screaming fans. A heated bout where both participants throw jabs at each other and launch haymakers hoping to land a knockout blow; and it’s all for money. A bloody display of barbarism and competition not unlike the violent exhibitions of Roman gladiators. That sport … is called politics.

Unlike boxing, politics is brutal. That’s why every election cycle, researchers nip at their nails nervously. Watching on and rooting for their prizefighter, their political candidate, to win.

But why? Why would researchers have this much emotional investment in an election?

First, a little history

On a sweltering June 2 afternoon in 1875, a young man named Thomas A. Watson sat in a warm room, perspiring intensely and staring at a length of wire on the dingy floor. The wire ran some sixty feet down the hall and to the other side of the building. On the other end of the wire another young man sat impatiently in a separate room. His name was Alexander Graham Bell, professor of vocal physiology and elocution at Boston University. In just a few moments, both men would set on a course that would change mankind forever. They’d send the first transmission of several messages over the wire at the same time, sans interference. The device they used was called the harmonic telegraph. The progenitor of the telephone and, eventually, the pocket computers we walk around with today.

In order to fund the development of this invention, Bell went to the father of one of his students, Mabel Hubbard, who would later become his wife. Her father elected to fund him and the rest was history.

You see, before federal funding, finding money for research and development was pretty simple. You got it from a “guy that knows a guy.”

That all changed when Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act into Law. This made it possible for states to sell federal land to fund colleges that concentrated on agriculture or engineering. Soon, the country was peppered with “land-grant colleges.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) founder William Barton Rogers persuaded the state to give MIT part of its land-grant fund in exchange for agreeing to teach its students military instruction. This newfound influx of government funding presented MIT as a worthwhile investment to private donors.

In 1919, Rogers spearheaded a campaign called the Tech Plan, an ancestor to modern technology parks. Thanks to this plan, MIT was reborn, this time buoyed by corporate patronage. The institution even created a Division of Industrial Cooperation and Research — a predecessor to today’s pervasive tech-transfer offices — to oversee corporately backed research projects at the university.

Corporate funding of research and development hit a land mine with the stock market crash of 1929. The stark reality of a moribund economy throughout the 1930s pushed MIT to do what many fiscally conservative administrators and even researchers and scientists were unanimously against: federal funding.

What’s the big deal about federal funding anyway?

According to the National Science Foundation (NSF), federal support for research makes up over half of all university research. Without federal funding, university research will suffer, and in turn, so will the public. Think about this: when the Ebola outbreak ravaged West Africa, it was a cluster of research universities that sent their lab and clinical assets to help treat and manage the virus. The benefits of university research surround us every second of every day. Touch screens, lithium-ion batteries, fluoride toothpaste, GPS, solar power, radio, insulin, numerous vaccines, ultrasound, CAT scan, MRI scanner, the internet (the internet!) and Gatorade have their roots in university research. How far would these innovations have gotten without half the funding? “Some of the benefits of basic research are obvious. It helps American families lead healthier lives through amazing new drug treatments and medical devices, better nutrition, and cleaner air and water,” said Richard Atkinson, former director of the NSF from 1977-80 and former president of the University of California, in his San Diego Union-Tribune piece “Why Federal Funding for Basic Research is Important.”

“Indeed, almost all of the technological advances of the past 50 years are linked to improvements in fundamental knowledge — much of it stimulated by federal research dollars,” he continued.

The politics of the penny

So, what do elections have to do with federal funding? Can’t every administration just hand over a check?

If only it were that simple. Elections present candidates that represent different parties. Each major party has its own reputation for science support. The research community might feel that one party in particular has more support for university research funding than the other. But presidential elections aren’t the only political battle the research community should be watching.

“Presidents can influence the allotment of resources for higher education through the bully pulpit, but in terms of elections, higher education advocates should pay close attention to who is elected to Congress,” said Renee Cross, the senior director at the University of Houston Hobby School of Public Affairs.

Similarly, the election of state legislators is a critical part of the state funding component of higher education, particularly in a state such as Texas, which limits the power of the governor,” she continued.

Proof that the power of the purse still lies with Congress is in the fact that during the Trump presidency, Congress has actually boosted research funding despite the administration’s proposed cuts to basic and applied research by $12 billion.

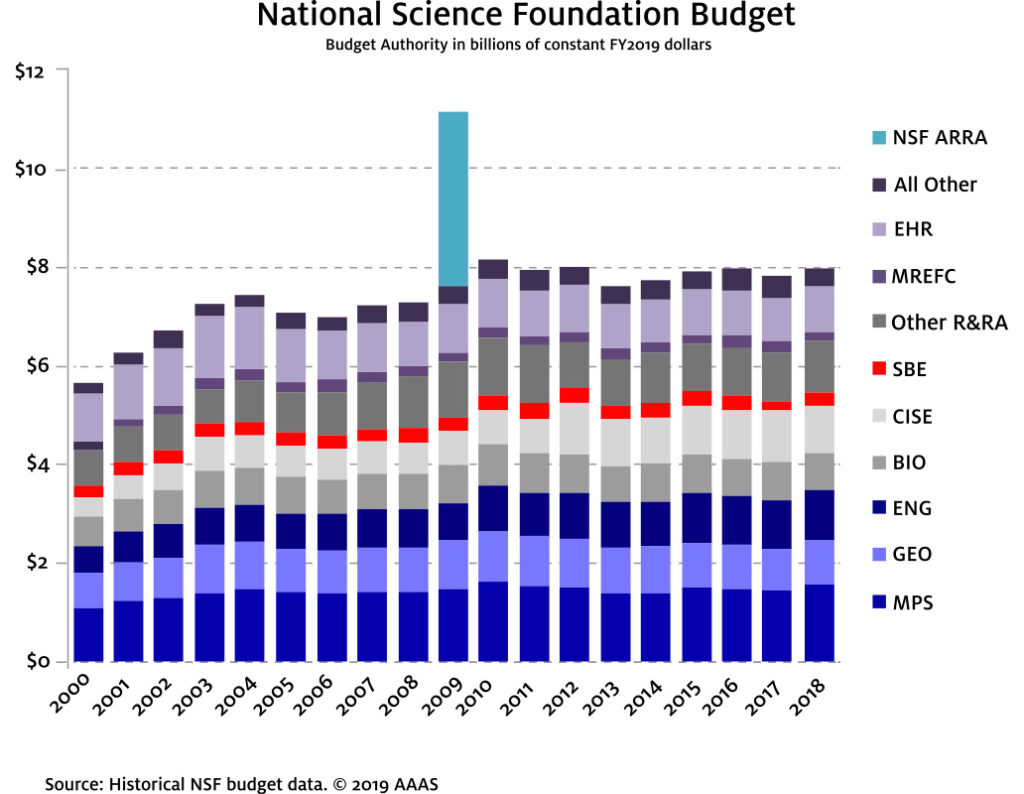

“From the beginning, the Trump Administration has taken a hard fiscal line on most research and development programs, favoring Department of Defense technology development and acquisition at the expense of basic and applied research, even Defense research activities,” explained Matt Hourihan, director of the R&D Budget and Policy Program for the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in his article “R&D in the FY 2020 White House Budget: An Overview.”

“But these proposals have been rather emphatically rejected from the start, beginning with the FY 2017 appropriations, which Congress began under Obama but didn’t finish until Trump. That spring, the Trump Administration recommended late-breaking cuts, but Congress ended up providing a mix of increases,” Hourihan explained.

It has been the same story since 2017, including a historically substantial FY 2018 omnibus and a recent 2019 omnibus that have given research agencies tons more to spend today than at the beginning of the president’s term.

Politics and PI panic

2016 brought about big change in America. A new administration brought forth new ideas, a different worldview and certainly a different economic disposition. Maybe a little too different.

The panic on the streets of America during this time seeped its way into the sterile, pristine labs of university research centers.

“It’s no secret that faculty are a little antsy,” Kalliat Valsaraj, vice president for research and economic development at Louisiana State University, told Politico in a 2016 interview. “They all wonder where the policies are going to go, where the funding is going to go. We’re all, as leaders, trying to remain calm. We have an opportunity to influence.”

The anxiety in 2016 reached a fever pitch just minutes after the new president was announced, with Ph.D. students and scientists taking to Twitter to announce their fears and displeasure.

Following the 2016 presidential election, researchers across the country feared a dramatic shift in federal funding.

The funding fears

“There is little doubt that research funding priorities change when a new administration arrives. And this is not necessarily partisan either. Each presidential administration is unique,” explained Jim Granato, the executive director of the Hobby School of Public Affairs.

Every new administration brings about a set of expectations within the research community. Researchers might expect less support from one party than another. More times than not, however, that party is the Republican party.

“Due to the political parties’ ideological differences about government spending, with traditional views of Republicans aiming to keep expenditures low and Democrats pursuing increased spending on centralized programs, most people assume that federal funding on higher education and other areas will increase with a Democrat in the White House and a Democratic majority in Congress,” said Cross.

Are these assumptions justified?

Just looking at the recent history of federal research funding, there is evidence that the blue party seeks more funding for research while the red party seeks more cuts. But there is also evidence that Republicans champion funding, too. Yes, it’s true that President Trump has sought to cut funding every year of his term so far, while Barack Obama sought to increase funding every year of his second term. But it’s also true that under the current administration federal funding for research has actually skyrocketed, even in the two years President Trump had a majority Republican Congress.

When asked if there has been more concern about federal funding when the government is Republican-led vs. Democrat-led, Jim Granato explained, “That might be the popular perception but it is not accurate because priorities shift. I can recall discussing this with my NSF colleagues (some with decades of experience) and – in the case of NSF – their view was the NSF did better under Republican Administrations.”

So was the panic justified? This is the part where you’re probably expecting a cop out answer like “yes and no.”

Well, you guessed right. The answer is yes and no.

No, the panic may not be entirely justified as it relates to the funding of research, since we saw a boost in research funding under a Republican president, including two years with a Republican majority Congress to boot.

And yes, it is a bit justified given the intentions of Obama’s second-term Republican majority Congress to appropriate less than what he requested in his budgets. Add to that President Trump’s proposed cuts to funding and one can see why anxiety might linger over the heads of researchers.

“The concern about support for science turned out to be mainly unfounded in that Congress has continued to support budget increases for science agencies, although the administration has not supported those increases in the President’s budget requests to Congress,” said Norman Bradburn, senior fellow at the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago and former assistant director for social, behavioral, and economic sciences at the NSF.

Surely, the concerns over the 2016 election were more nuanced than to just be about funding alone.

“In practice, funded research areas are more likely affected by which party is in office than how much funding is made available. For example, a few years ago, a number of Republican congressional members pushed to substantially decrease the NSF’s support of social science, particularly political science,” said Cross.

She continued, “The aim was to limit social science grants to research solely pertaining to national security and economic interests. In this case, the primary issue was not necessarily the amount of funding, but what exactly the federal government would fund (emphasis added).”

And therein lies the nuance. It wasn’t just about funding, but what the administration might choose to fund and choose to cut. So, is research funding the only reason for continuing PI panic and research community anxiety?

“It depends on who you talk to since the practice of science can fall victim to politicization – within the scientific community. Thomas Kuhn warned us about this years ago. One issue in this current period, that is quite explosive, revolves around climate change research and regulations. The Trump Administration clearly has a different view on this issue than the Obama Administration,” said Granato.

Political climate change

Most people are not sure what’s more concerning, the political climate or the actual climate. The issue of climate change has taken the spotlight again when it comes to science and politics. When asked what he felt were the biggest concerns in the research community regarding the 2016 election, Bradburn replied, “The two biggest were whether budgetary support for science would continue at a high level in the new administration and whether science would continue to be listened to in deciding about regulations, particularly those concerning climate change.” One of the biggest reasons for these concerns was the president’s rhetoric during his debates, speeches and interviews leading up to his presidential victory. During this time, he vowed to cancel the Paris climate agreement, which as we know, eventually came to fruition.

“If Trump steps back from that, it makes it much less likely that the world will ever meet that target, and essentially ensures we will head into the danger zone,” said Michael Oppenheimer, a professor of geosciences and international affairs at Princeton University and a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which produces global reports on the state of climate science.

Asked if the 2016 election concerns in the scientific community regarding climate change were unfounded or substantiated in the last four years, Bradburn remarked, “(It) has turned out to be true, and science advisory committees to agencies, particularly those related to climate concerns, have been decimated and scientific advice has been rejected or downplayed in many agencies.”

Hindsight is 2020

Looking back now, we can see, quite clearly, that there were definitely reasons for concern in the scientific community regarding the election of President Trump, but there was also reason to think the hysteria might have been inflated. Whereas concerns of budget cuts were realized, as the president did indeed propose myriad budget cuts to research funding, Congress defied expectations and granted funding beyond what was requested. While funding concerns were predominantly quelled, the issue of climate change and the downplaying of the voice of the science community in matters like climate change is still very much alive. “There is less concern about the future of funding for science agencies because of strong Congressional support for NIH and NSF as well as the Defense Department and NASA, but there is a fear that the President’s reelection will further erode the role of science in important policy areas, particularly those related to climate,” proclaimed Bradburn.

The research community has every justification to be nervous about any election. They want to make sure they avoid the jab of a funding cut, the right hook of anti-science politicking, and the knockout blow of science suppression. Indeed, politics is a brutal affair not unlike boxing. In boxing the competitors only hurt each other. In politics they hurt each other but can hurt everyone around them. 320 million people to be exact. The decisions they make reverberate throughout every facet of culture, society and science. From voting booth to laboratory. From poll to PI. From election to electron.